Using the principle of "doing right" to better understand medical ethics

Medical ethics is vital in many elements of the application process (the SJT section of the UCAT, and interviews), as well as during medical school and later on in prospective medic’s careers.

The most common approach medical applicants use is to learn the basics…

The Four Pillars of medical ethics: Beneficence (doing good); non-maleficence (doing no harm); Autonomy (giving the patient the freedom to choose freely, where they are able) and Justice (Ensuring fairness).

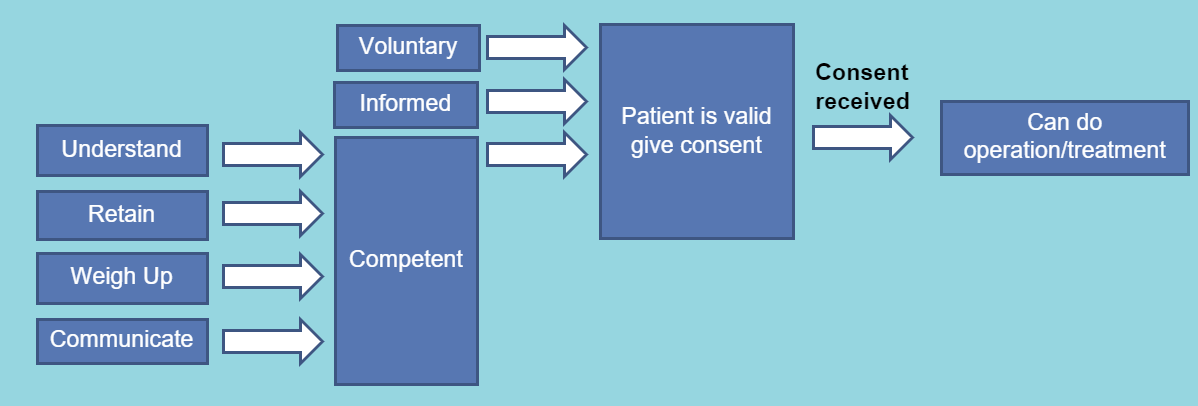

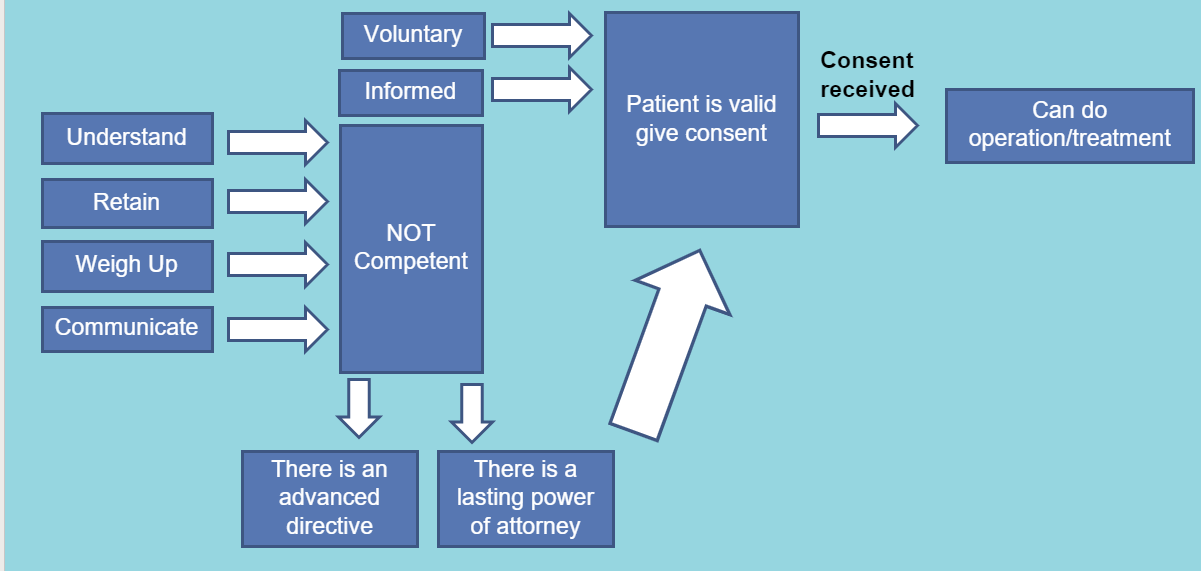

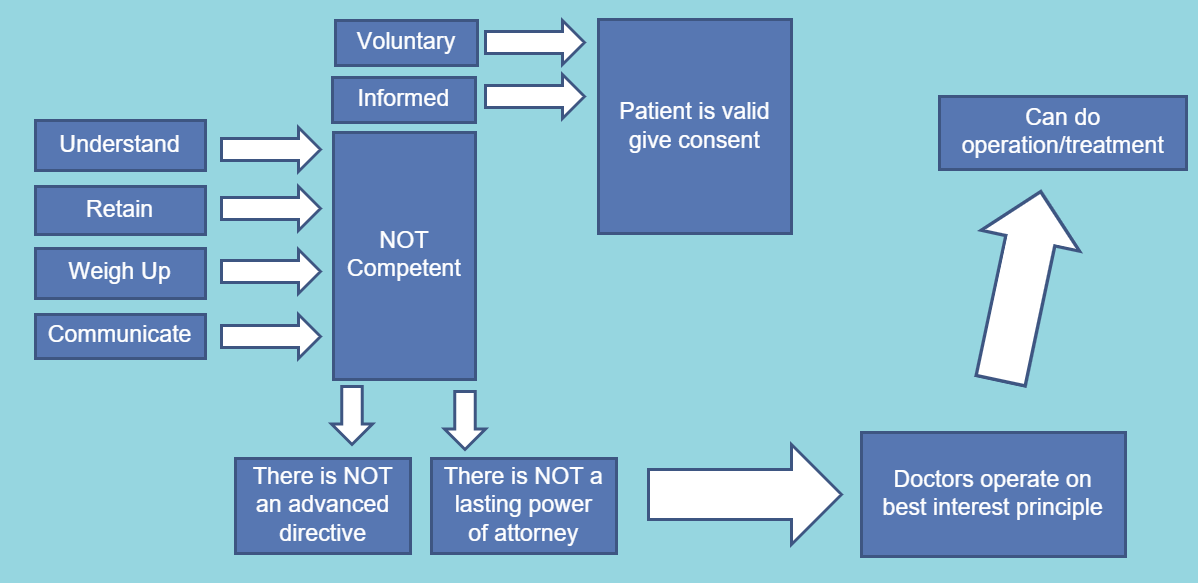

Competence and consent (flow diagrams from the author below illustrating these concepts).

Gillick Competence. The Gillick test states that if a minor possesses “sufficient intelligence and understanding to enable them to understand the treatment then they are ‘Gillick competent’ and can consent to treatment,” but can’t withdraw consent

The Fraser Guidelines. The guidelines state that contraceptive advice or treatment can be provided to a child under 16 without parental consent or knowledge provided that the healthcare professional is satisfied:

1. That the individual will understand the advice.

2. That the professional cannot persuade them to inform their parents or allow them to inform the parents that they are seeking contraceptive advice.

3. That they are likely to begin or to continue having sexual intercourse with or without contraceptive treatment.

4. That unless they receive contraceptive advice or treatment their physical or mental health or both are likely to suffer.

5. That their best interests require the professional to give them contraceptive advice, treatment, or both without parental consent.

Although useful, I have found that with more complex medical ethics scenarios, especially those presented to you during medical school interviews, a greater understanding of medical ethics is required. Having achieved band 1 in the SJT and been successful in all 4 medical school interviews, I can say that following the principle of “doing right” will ensure your success.

Book of the week: Better: A Surgeon's Notes on Performance by Atul Gawande

This week’s theme of doing right is the topic covered by Gawande in the second section of his book “Better.” The author draws upon 5 key stories, 1 of which will be covered this week:

“The Doctors of the Death Chamber.” Gawande opens with an unprecedented ruling from an American district court in 2006 concerning the execution by lethal injection of Micheal Morales. Said ruling ordered a physician (specifically an anesthesiologist) to personally supervise the execution. Why? The judge found that there was a possibility that prisoners undergoing lethal injection suffered suffocation from drugs given before the paralytic agent, feeling intense pain. This would be unacceptable under the 8th Amendment in the American Constitution against cruel and unusual punishment. On this court’s ruling, the Californian and American medical association of Anesthesiologists responded with opposition to such physician participation, as it was a clear violation of medical ethics codes: “Physicians are healers, not executioners.” With the ruling still standing, today execution has become a medical procedure in the USA. On commenting on this policy, Gawande claims:

“This (the policy) forced doctors and nurses to choose between the ethics of their professions and wider society, neither is always right. There are sometimes blurry differences between acting skillfully, acting lawfully, and acting ethically.”

Gawande finishes the introduction by raising the question of whether nurses and doctors are always allowed to refuse involvement in lethal injections, but some don’t- who are they? And why do they choose to be involved? For the rest of the section, Gawande recounts interviews with such doctors.

First was Doctor A. He had a warden officer of a local prison as one of his patients who asked him to help at said prison- doctor A accepted. He would have made more money in his own clinic per hour, but the prison was important to the community. Doctor A knew about the past of some of the prisoners, and the terrible crimes they committed and felt this justified the executions. He said he was only helping with monitoring and further justified his involvement by claiming:

“I am needed by the warden and my community; the sentence is society’s order, and the punishment is not wrong.”

However, he slowly began seeing that the prison staff would ask him to take more responsibility in situations when things went wrong- going as far as putting in the IV himself. He was getting close to being the executioner himself. As a result, he was challenged in court, on his office door one day he saw a sign that said, “The killer doctor.” Although he was protected by law he decided to quit after being challenged in court.

Gawande then recounts his conversations with Doctor B. Doctor B became involved long ago when electrocution was the primary method and continued through to transition to lethal injections and he remains a participant to this day. However, he was more cautious and reflective about his involvement than Doctor A and he seemed more troubled by it. He had no moral objections to capital punishment. Knowing the guidelines, he drew clear boundaries, only pronouncing death and not assisting in any other way. However, Doctor B is still troubled by the process claiming that:

“The trouble is not that the lethal injection seems cruel but from my doubts about if anything is accomplished. I really wonder if lethal injection lowers the incidence of anything.”

Looking at his conversations with Doctor C, Gawande reports that this doctor is younger than the others. Doctor C uses the following line of reasoning to justify his involvement:

“Members of the state have made a decision and if I live in that state then it is an obligation to be available. If someone I loved had to be put to death, I would want it to be done by lethal injection and for it to be done competently.”

Unlike the others, Gawande highlights how Doctor D works on many humanitarian campaigns and opposes the death penalty as he regards it inhumane, immoral and pointless. Despite this, Doctor D actively participates in executions by lethal injection. A jail opened up near the hospital where Doctor D worked, overtime he was involved more in treating prisoners in jail. Although he opposed the death penalty, there were needs he thought that a correctional physician could serve. He felt an obligation to not abandon inmates in their final moments. Further justifying his involvement, Doctor D claims:

“This is an end-of-life issue, just like any terminal disease. It is just that it involves a legal process rather than a medical one. A death penalty patient is no different from a patient dying of cancer, but his cancer is instead a court order.”

Doctor D’s “cure” for the death penalty is its abolition but if the government and the people won’t let you provide it, and a patient then dies- are you not going to comfort them? He is involved in the process and says his task is to ensure that the prisoner’s death is as painless as possible. If you are more interested in Doctor D, you can read his full story at this link.

Figure 1- Doctor D (retrieved from article linked)

Reflecting on Doctor D’s points, Gawande asks How can the conflict between government efforts to provide a medical presence and our ethical principles forbidding it, be resolved? Are our ethics what should change? The author then goes on to argue that however strong Doctor D’s argument is, inmates are arguably not patients. They cannot refuse the doctor’s “care”. Medicine is being made an instrument of punishment, and we cannot escape this truth. Adding to this point, Gawande claims:

“If execution by lethal injection cannot be done without medical staff present in a humane way, the death penalty should be abolished. It is not clear whether a society which punishes its worst criminals with life in prison is worse off than on that sentences them to death. But a society in which the government subverts core ethical principles of ethical practice is worse off for it. As our ability to manipulate bodies advances, government interest in our skills will only increase. Preserving the integrity of medical ethics could not be more important.”

Additionally, the author argues:

“The public has given their trust to medical staff to put them under anesthesia, cut them open and do what would otherwise be considered assault, as we do so to improve the quality of their lives on their behalf. For the state to use these skills against a human being for punishment seems a dangerous perversion. Society has entrusted us with powerful abilities and the more we are willing to use these abilities against individual people, the more we are risking destroying this trust.”

Gawande ends this section with a comment on how each of us -medical or not- has a duty not to follow rules and laws blindly. He goes on to argue that in medicine, people face conflict in what the best actions are in all kinds of areas (e.g. abortion). In addressing this Gawande claims that:

“We must do our best to choose intelligently and wisely, sometimes however we will be wrong. We each should then be able to face the consequences, above all we must be able to recognize when using our abilities skillfully comes into conflict with using them rightly.”

Thanks for reading,

The Vansoh is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.