On “Ingenuity” and its application in studying

It is no lie that S6 for a medical school applicant is a challenging year, balancing UCAS applications, advanced highers, interviews, work experience and personal statements. Something I, as many of my friends, underestimated was the challenge of studying efficiently for the much more difficult advanced highers while also having less time available to actually study due to the application process. Having conducted my own research and reflecting on my own experience in S6, as well as those of my friends, I have found one technique has helped massively. Yes there are the ubiquitous mantras of “do practice papers,” and “read the mark scheme,” which are useful but something I feel is less obvious is the power of shifting to studying on a tablet. This is where this week’s theme of “ingenuity” comes into play.

Defined by Gawande as “the willingness to recognize failure, and to be open to change,” Ingenuity perfectly describes the mindset necessary to make the shift from paper based learning to tablet based. So why should you make the change?

Why taking notes is important? It’s a way of transcribing what is in your head and combining your thoughts together. The traditionally offered ways to take notes: typing things up or handwriting them both have their own flaws.

Typing up notes: The process of sitting down and just typing may not be engaging and thus unsustainable for a long enough time to allow you to learn. Moreover, the system of typing left to right with even spacing and perfect fonts inevitably puts constraints on your note-taking ability. What if you want to annotate a diagram? What if you want to draw a diagram? Having said this, the positives of typing up notes is that files are saved so cannot be lost and if you find a new piece of information you can insert it into your notes.

Hand writing notes: Gives you the freedom to bring things together in a way that wouldn’t be possible if you typed them up. However, this technique also has downfalls: what if you make a mistake? What if you wanted to add something to it later? What if they got lost?

Using a tablet to take notes: A tablet is a device that essentially gives you all the benefits of taking notes typed up on a computer along with all the freedom you get with handwriting your notes. I can say that my tablet of choice (ipad Air) delivers on this. The only regret I had was not switching to a tablet sooner!

Book of the week: Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance by Atul Gawande

This week’s theme of ingenuity is the topic covered by Gawande in the third section of his book “Better.” The author draws upon 3 key stories, one of which will be covered this week.

“The Score.” Gawande opens with the story of a patient in the late stages of pregnancy, a doctor herself, she had delivered babies and wanted a vaginal delivery. She wanted control of her delivery. She wanted a delivery “as nature intended”:

“I didn’t want intervention, no drugs, I didn’t want any of that. In a perfect world I would want to have my baby in a forest hut attended by fairy sprites.”

It is revealed that she eventually broke down after some complications with her delivery and ended up having to get a caesarean section after a failed epidural. Gawande uses this anecdote to illustrate how despite human’s understandable desire to control child birth it is an intricate process that is unpredictable in nature. Gawande then introduces the idea of the evolutionary problem of how an animal can walk upright -requiring a small fixed bony pelvis- and also possess a large brain which enables a baby whose brain is too big to fit through said small pelvis. Part of the solution is how in a sense all humans give birth prematurely. In stark contrast to other mammals, which are born mature enough to walk and seek food within hours, our newborns are small and helpless for months. Gawande goes on to further emphasize how complex childbirth truly is and -importantly- how easily things can go wrong at any step of the process. So much so that for thousands of years childbirth was the most common cause of death for young women and infants; puerperal fever was the leading cause of maternal death in the era before antibiotics. The technique of choice prior to the widespread use of caesarean sections was the obstetrical forceps.

By the early 20th century, the problem of human birth seemed to be solved. Doctors could use a range of measures: antiseptics, foreceps, blood transfusions, labor-inducing drugs and even cesarean sections. However, despite the shift of mothers from home deliveries to hospitals, in 1933 a shocking study published found that around 2/3 of maternal deaths were preventable. There had been no improvement in the death rates for mothers in the preceding two decades, to make matters worse the death rates for newborns actually increased. Mothers were better off delivering at home. Why? Physicians simply didn’t know what they were doing, they missed clear signs of treatable conditions, violated basic antiseptic standards and misapplied forceps. This revelation brought modern obstetrics to a turning point. Specialists in the field had shown extraordinary ingenuity: developed the knowledge and instrumentation to solve many of the problems of child delivery. Yet knowledge and instrumentation had proved grossly insufficient, if obstetrics wasn’t to die out it had to discover a different kind of ingenuity. It had to figure out how to standardize childbirth.

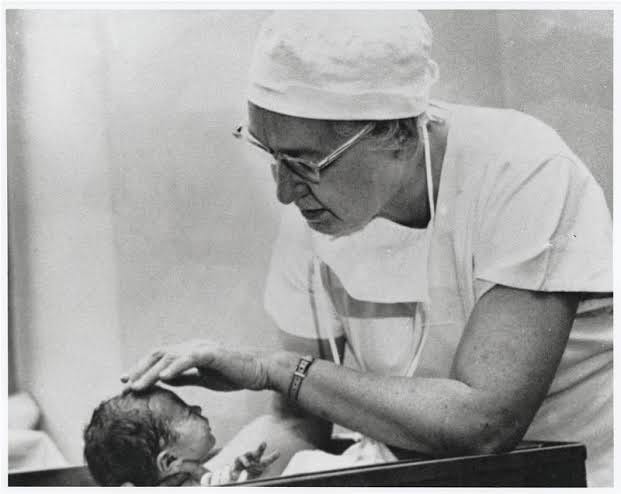

The 1930s report showed that obstetrics had failed. In response governing bodies and hospitals put strict regulations into place. As a result of this regulation and the introduction of penicillin, the maternal death rate during childbirth fell by 90%. However, there was not as much success in reduction of the newborn death rate. This is where the author introduces Virginia Apgar (shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1- Virginia Apgar1

Apgar was the first woman to be admitted to the Colombia college of surgeons and physicians. An anesthesiologist herself, she found herself being appalled by the care babies received. In response to this she devised a score: the Apgar score. This allowed nurses to determine the condition of babies at birth on a scale from 0-10. This ingenuity turned a intangible clinical concept -the condition of new babies- into a score that could be used to compare different babies. Using it required more careful observation and documentation of the true condition of every baby, moreover it drove doctors to produce better scores and thus better outcomes for the patients they delivered. Babies with bad Apgar score at one minute could be raised to a good score within 5 minutes, contributing to the advent of neonatal care units. The score also altered how childbirth itself was managed, spinal and epidural anaesthesia proved to produce better results that general anaesthesia for example. Over the years hundred of adjustments and innovations in care resulted in impressive results. To highlight the magnitude of these results, Gawande draws upon statistics:

“In US today only 1 in 500 children die, and a mother dies in less than 1 in 10,000. If the statistics of the 1930s persisted, 27,000 mothers would have died last year rather than less than 500 and 160,000 newborns rather than less than 1/8 that. ”

Shifting the focus of the section, the author then explores a paradox:

“Ask most research physicians how a profession can advance and they will tell you the model of evidence based medicine (the idea that nothing ought to be brought into practice unless it has properly been tested and proved effective by research centers). But in 1978, ranking for specialities by their use of hard evidence from randomized clinical trials, obstetrics came in last.”

Gawande then looks to the example of fetal heart monitors to illustrate this.

“Careful studies show fetal heart monitors add no added benefit over routine labour over nurses simply listening to the heart rate hourly. Yet they are used in almost all hospital child deliveries.”

The paradox lies in the fact that despite obstetrics apparent poor performance on their use of “hard evidence from randomized clinical trials,” nothing else in medicine has saved lives on the scale that obstetrics has. Although the author admits that there have been amazing innovations in what we can do to better treat diseases in other specialities (e.g coronary artery stents, mechanical joints and artificial respirators), he argues that “no one in medicine… uses these measures as reliably and safely as obstetricians use theirs.” In order to illustrate this point Gawande compares the approach taken to treat pneumonia to those used in child delivery. On discussing pneumonia Gawande claims:

“Elegant research trials have shown the best antibiotics to use, and that patients needing hospitalization are less likely to die if the antibiotics are started within 4 hours of arrival. But we pay little attention to what has actually happened in practice. A study found that 40% of patients do not get the antibiotics on time and when we do give the antibiotics, 20% of patients get the wrong kind.”

The author juxtaposes this to what is done in obstetrics where…

”Doctors did not wait for research trials to tell them if it was alright to carry out a certain procedure. They just went ahead and tried it to see if results improved. So they improved on the fly but always paid attention to results and tried to better them. And that approach worked.”

However, Gawande does admit that wether all the adjustments and innovations of the obstetrics package are necessary and beneficial is currently unclear. But that the package as a whole has made child delivery much safer and has done so despite the increasing age, obesity and consequent health problems of pregnant mothers.

Returning to his main point, Gawande then argues that the Apgar effect wasn’t just that of giving clinicians a quick and objective read of the available data, the change also changed the choices they made about how to do better. Chiefs of obstetric services starting pouring over the Apgar scores of their doctors. Gawande uses an ingenious comparison to illustrate this “Apgar effect:”

“They (obstetricians) became no different from factory managers. Both want solutions that will lift the results of every employee. That means sometimes choosing reliability over the rare cases of perfection.”

Building on this comparison, the author uses the fate of the forceps as an example. He claims that although many studies showed fabulous results for foreceps, they only described how well forceps could perform in the hands of very experienced obstetricians at large hospitals. This lead to a question that faced all obstetrics, is medicine a craft or an industry? In trying to find an answer, the author asserts

“If medicine is a craft then the focus should be on teaching obstetricians a set of artisanal skills and conducting research for new ways to operate. But if medicine is a industry, responsible for safest possible delivery, then a new understanding is required.

Having spoken to a renowned professor in obstetrics, Gawande concludes that:

“After Apgar, obstetricians needed a simpler and more predictable way to intervene if things went wrong, hence the rise of caesarean sections.”

Gawande uses this point as a segway into a discussion of the debate that arose from said rise of caesarean sections, around wether a mother in the 39th week of delivery should be offered delivery before going into labor. The author argues against this suggestion, claiming that:

“It seems to show the worse kind of hubris. How could a Caesarian delivery even be considered without trying a natural one? It would be like a healthy patient being offered artificial hips as they are stronger than natural ones.”

On the other hand, the author argues that obstetricians have reason to believe that this 39 week delivery by caesarean section could reduce mortality rates in babies and mothers. Additionally, the author notes that a study in Israel and Britain showed caesarean sections had lower mortality rates than natural birth. Despite this, the author still expresses hesitation to adopting this new technique:

“The rise of the caesarean section also marks us losing connection to yet another natural process of life.”

Additionally, Gawande makes the point that putting so many mothers through surgery is hardly cause for celebration but also stipulates that the desire to reduce risk to babies is the biggest force behind caesarean sections prevalence. The author concludes with a compelling general point:

“In a sense there is a tyranny to the score, while we rate the newborn child’s health, the mother’s pain and blood loss and recovery seem to count little. We have no score for how the mother does, beyond asking wether she lived or not. If the child’s well-being can be measured why not the mother’s too?

Gawande uses this line of reasoning to argue that an Apgar score is needed for everyone who encounters medicine. In fact, his research group came up with a surgical Apgar score from 1-10. His motivation behind this:

“There is no reason we cannot aim for everyone to do better.”

Thanks for reading,

The Vansoh is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate our work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/cp/feature/biographical-overview